Mexican drug cartels use hundreds of thousands of guns bought from licensed US gun shops – fueling violence in Mexico, drugs in the US and migration at the border

The Mexican security forces tracking Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes –

the leader of a deadly drug cartel

that has been a top driver of violence in Mexico and narcotic addiction in America –

thought they finally had him cornered on May 1, 2015.

Four helicopters carrying an arrest team whirled over these mountains near Mexico’s southwestern coast

toward Cervantes’ compound in the town of Villa Purificación, the heart of the infamous Jalisco Nueva Generación cartel.

As the lead Super Cougar helicopter pulled within range,

bullets from a truck-mounted, military-grade machine gun on the ground struck the engine, forcing an emergency landing. Before it reached the ground, the massive helicopter was also hit by a pair of rocket-powered grenades.

This .50-caliber cartridge was found stuck in the truck-mounted Browning M2HB machine gun that the Jalisco Nueva Generación Cartel used to damage a Mexican Security Forces Super Cougar helicopter. Source: ATF

This .50-caliber cartridge was found stuck in the truck-mounted Browning M2HB machine gun that the Jalisco Nueva Generación Cartel used to damage a Mexican Security Forces Super Cougar helicopter. Source: ATF

Four soldiers from Mexico’s Secretariat of National Defense were killed in the crash. Three more soldiers were killed in the firefight that followed, and another 12 were injured.

The engagement was the first known incident of a cartel successfully shooting down a military aircraft in Mexico. The cartel's retaliation for the attempted arrest was swift and brutal – and aimed at creating chaos. It hijacked fire trucks and buses and set them ablaze on roadways to create blockades. It set fire to banks, gasoline stations and private businesses. In total, 25 municipalities reported severe acts of narco-terrorism across the Mexican states of Jalisco, Michoacan, Nayarit and Guanajuato. There were four major shootouts in the surrounding areas that day.

The distractions worked. Cervantes, also known as “El Mencho,” escaped.

The Browning machine gun that took down the helicopter was eventually

traced back to a legal firearm purchase in Oregon made by a U.S. citizen.

And a Barrett .50-caliber rifle also used in the ambush

was traced back to a sale in a U.S. gun shop in Texas 4½ years before.

These are far from the only military grade weapons trafficked into Mexico from the U.S.

Each year, tens of thousands of them flow across the border, aided by loose standards for firearm dealers and gun laws that favor illicit sales. Meanwhile, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives – the agency known as ATF tasked with regulating the industry – is beset by criticism on the left and right for not doing more to regulate an increasing number of guns.

We – a professor of economic development who has been following and tracking illegal gun trafficking for more than 10 years, and an investigative journalist – spent a year sifting through documents and traveling to Mexico to follow the flow of illicit weapons trafficked from the U.S. to Mexico.

Despite the millions of illegal firearms in Mexico, there has been little research done on estimating the number of guns trafficked into the country. Estimates of the annual illegal flow over the years have ranged from 200,000 to nearly 600,000, but few of these figures cite a rigorous methodology to arrive at their conclusions. Some agencies base their number directly off a study one of us did over a decade ago that estimated an average of 253,000 firearms being trafficked across the border each year from 2010-2012. Accurate data on the scale, scope and consequences of U.S.-sold weapons in Mexico are needed to inform policy responses.

Part of this ambiguity is the result of federal law, which restricts the detail of traced firearm data to researchers and the public. The ATF publishes the number of U.S. guns seized in Mexico and traced back to U.S. dealers, but it does not provide an official firearms trafficking estimate.

We set out to fill the gap in knowledge about the number, origins and characteristics of weapons flowing from the U.S. to Mexico.

We combed through detailed ATF firearm data on guns trafficked to Mexico and traced back to U.S. dealers. The records were buried in a cache of about 10 million emails pulled from the servers of the Mexican government by the hacktivist group known as “Guacamaya” in September 2022. The emails were obtained through the U.S.-based Distributed Denial of Secrets, a nonprofit repository of hacked and leaked data. This dataset contains close to 24,000 detailed firearm records from December 2018 through November 2020 that were recovered in Mexico and traced back to their origins. More than 15,000 of the firearms had been traced by the ATF back to the U.S.

We also reviewed 100 U.S. court cases from 2006 to 2024 that referenced over 4,200 firearms involved in the trafficking of weapons into Mexico.

We combined these two sets of firearm trace data with half a dozen other datasets from U.S. and Mexican authorities. We used these comparisons to estimate the number of weapons trafficked from the U.S. to Mexico each year, identify characteristics of dealers to which trafficked guns have been traced, examine relationships between guns trafficked and state gun laws, and find what effect regulations might have on the trafficking flow.

To estimate weapons flow, we gathered trafficking estimates and combined them with previous research, firearm manufacturing totals and the ATF trace data. We generated a model that arrived at a conservative middle estimate: About 135,000 firearms were trafficked across the border in 2022.

By way of comparison, consider that Ukraine, engaged in a war with Russia, received 40,000 small arms from the United States between January 2020 and April 2024 – an average of 9,000 per year. That is just under 7% of the trafficked firearms flow that our model showed from the U.S. to Mexico.

Our analysis also found:

This flow of weapons is connected to the drug trade in the U.S. and is enabling increased gang violence in Mexico, causing more people to flee across the border.

An increase in guns trafficked to Mexico from the U.S. is directly related to a significant increase in Mexico’s homicide rate.

The most destructive weapons are more likely to come from independent gun dealers than large chain stores.

Independent dealers sell 16 times as many assault-style weapons and 60 times as many sniper rifles to people.

The flow drives an arms race between criminals and Mexican law enforcement, to the benefit of a U.S. gun industry that profits on sales from both ends.

ATF oversight of dealers reduces the likelihood their guns are resold on the illicit market.

A federal agency hamstrung

Why is such an intensive investigation to estimate the number of guns flowing across the border needed? It is because there are enormous gaps in tracking guns that are bought in the U.S. and recovered in the U.S. and in other countries.

The rules used to be stricter. Decades ago, the ATF had more enforcement authority, firearm dealers were held to a higher standard when making sales, and federal gun data could be shared with the public to hold problematic dealers accountable.

But in 1978, Congress began denying funding to the ATF. Then, the congressional report The Right to Keep and Bear Arms in 1982 established the argument of personal liberty in gun ownership. The report, produced by Republican leadership, is widely credited with centering the modern conservative stance on gun ownership around an individual's constitutional right to own guns. It castigated the ATF for overregulation, harassment of gun dealers and prosecuting people who otherwise lacked a felony record.

The report led to the Firearms Owners’ Protection Act of 1986, which, rather than protect individual gun ownership, curtailed the ATF’s ability to regulate the sale and production of guns.

In 2003, Congress passed the Tiahrt Amendments, which barred the ATF from creating a database of firearm sales and prohibited federal agencies from sharing firearm trace data outside of law enforcement. Congress later broadened the law to mandate that the FBI destroy information from successful background check applications within 24 hours and to bar the ATF from requiring dealers to do a physical inventory of their firearms. And after a federal ban on assault weapons lapsed in 2004, President George W. Bush signed the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act, which shielded the industry from civil liability lawsuits stemming from the use of their weapons.

U.S. firearm production surged. Handgun production grew nearly 550% from 2005 to 2022 – jumping from a little over 1 million weapons to just over 7 million, before dropping to 4.7 million in 2023, according to ATF manufacturing reports. Rifle production also rose 150% during that time, from 1.4 million to 3.6 million before dipping to 3.1 million in 2023.

Many of those weapons were trafficked into Mexico, where they have facilitated cartel control and fueled violence. From 2015-2023, just over 185,000 guns linked to crimes in Mexico were sent to the ATF to be traced – the process of using a firearm’s serial number and other characteristics to identify the trail of gun ownership. Around 125,000 of those weapons – more than two-thirds – have been traced back to the U.S.

These firearms were sourced from every state and range from palm-sized .22-caliber handguns to .50-caliber rifles that can shoot through a truck engine block from over a mile away.

Since 2008, the United States has spent more than US$3 billion to help stabilize Mexico through the rule of law and stem its surges of extreme violence, much of it committed with U.S. firearms. The gun industry and its supporters have undercut these efforts by fighting almost every measure to regulate gun sales. Many of the programs are funded through the U.S. State Department, which is facing budget cuts, and the U.S. Agency for International Development, which has sustained deep cuts, including programs in Mexico.

On Feb. 20, 2025, Kash Patel, President Trump’s controversial pick for director of the FBI, was confirmed by the Senate, and within a week he assumed control of the ATF as the bureau’s acting chief. Patel is widely seen as being friendly to the gun industry, and the news of his appointment was first reported by the Gun Owners of America, a Second Amendment lobbying organization that has advocated for the abolishment of the ATF.

Patel spoke at the lobbying group’s inaugural summit in 2024. Advocates and law enforcement organizations feared he would soon begin dismantling the bureau. In late March, a Justice Department memo suggested merging the bureau with the Drug Enforcement Agency. In the first few months of 2025, Patel was mostly an absentee leader before being abruptly replaced by the secretary of the Army in April.

Following the flow

Our analyses show that U.S.-Mexico firearms trafficking has dire implications for the lives of ordinary Mexicans – and one that U.S. regulatory actions can have an enormous impact upon. These analyses add to a growing body of research tying U.S.-sold guns to Mexico-based gangs and cartels, illegal drug trafficking, homicide rates, corruption of Mexican officials, illicit financial transactions and migration trends.

It is all because gun sales is a big business. As of March 2025, there were over 75,000 federally licensed firearms dealers, pawnbrokers, importers and manufacturers. By comparison, there were roughly 13,500 McDonald’s fast food restaurants in the country. Yet the ATF has historically had trouble ensuring that gun dealers receive at least one compliance inspection – a review of the licensee’s business to ensure they are conforming with federal laws – every three years. Most restaurants are inspected at least once a year.

Between 2016 and 2019, on average, 12% of licensed dealers were inspected each year, excluding those specializing in curios, according to the ATF’s May 2022 National Firearms Commerce and Trafficking Assessment. Inspections then plummeted to 5.8% of dealers during the 2020 pandemic; only in 2024 did they begin to reach previous levels.

If the ATF wanted to do more, it would be difficult: The agency is perennially underfunded and understaffed because the politicization of guns has made it a multiparty punching bag. Democrats have faulted the ATF for not doing more to enforce firearm laws, and Republicans have assailed them for harassing business owners.

In 2020, for instance, a collection of cities, led by Syracuse, New York, and the state of California and Giffords Law Center sued the bureau over its definition of a “firearm” in a successful attempt to regulate gun frames that people can use to make “ghost guns” – firearms that can’t be traced because they don’t have serial numbers. Meanwhile, in May 2024, 26 red states sued the bureau over its definition of what it means to be “engaged in the business” of dealing firearms to reduce enforcement actions against private individuals who sell guns.

The partisan fighting over guns has made it difficult for the ATF to secure adequate funding. According to its 2025 budget submission to Congress, the bureau has less than half the industry inspectors it needs to ensure that every dealer has a compliance inspection once every three years.

Meanwhile, the firearm industry continues to generate profits from legal transactions by licensed dealers who are often willfully blind to the criminal intentions of gun purchasers.

“If you want to take seriously this whole process for keeping guns out of the hands of people who our laws say are too dangerous to have them, you should have a vetting process that isn't facilitated by the person who has a vested interest in selling guns,” said Daniel Webster, distinguished scholar for the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions.

Webster reviewed The Conversation’s findings on how more oversight of dealers can lead to a lesser likelihood guns will be illegally resold and said they were in line with his research and experience.

Oregon guns tied to cartel

Today, the Jalisco Nueva Generación cartel is poised to be the biggest player in the drug cartel game. El Mencho, still at large, is one of the most powerful people directing the flow of heroin, fentanyl and methamphetamines into the United States, while orchestrating campaigns of fear, intimidation and displacement in Mexico.

And the guns the cartel uses were traced to the U.S. The Browning .50-caliber rifle that aided El Mencho’s evasion in 2015 was manufactured by a company based in Morgan, Utah, and legally sold to Erik Flores Elortegui, a U.S. citizen. The sale took place with a gun dealer in Rainer, Oregon.

Elortegui fled the country after he was indicted in Oregon for smuggling guns into Mexico and is now on the top of the ATF’s most wanted list. But according to Timothy Sloan, former U.S. ATF attaché in Mexico, it would be a lot of work and diplomacy to extradite him for violating a relatively weak law almost eight years ago. And years of prosecution might result in little prison time.

“You're not talking about a murderer who left DNA, a fingerprint, and the murder weapon at the crime scene. You're talking about somebody that lied on a piece of paper,” Sloan said. “It's a lying-and-buying, not the sexiest felony in American history.”

Elortegui wasn’t alone in his gunrunning schemes. According to a grand jury indictment, Elortegui purchased 20 firearms through an accomplice, Robert Allen Cummins, in 2013 and 2014. Cummins was straw purchasing – buying weapons under his name for Elortegui.

On May 7, 2014, Cummins purchased 14 rifles, including three Barrett .50-calibers, from Adaptive Firing Solutions, a licensed dealer run out of a nondescript storefront on Main Street in Oregon City, Oregon. The rifles were purchased all at once for $38,100 in cash and picked up a week later. Cummins passed the weapons to Elortegui, who then drove them to Calexico, California. There, he likely used a Dremel brand tool he purchased at Home Depot to grind off the firearms’ serial numbers before crossing the border into Mexicali, Mexico.

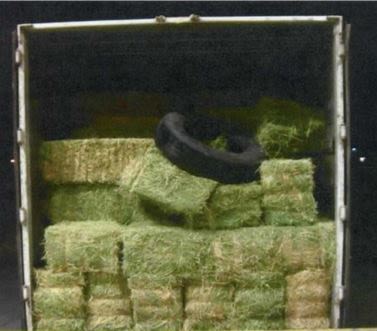

Some of the weapons that Cummins purchased for Elortegui were found later buried in alfalfa in this tractor trailer in Sonora, Mexico. USA v. Robert Allen Cummins, Public Domain

Some of the weapons that Cummins purchased for Elortegui were found later buried in alfalfa in this tractor trailer in Sonora, Mexico. USA v. Robert Allen Cummins, Public Domain

A month later, most of the weapons were found buried in alfalfa in a tractor trailer in the Mexican state of Sonora.

Cummins is a fifth-generation Oregonian who grew up in the wooded areas around Eugene. As a kid, he was afraid of guns, but, according to his court testimony, when he helped a friend sell weapons at gun shows, he felt important. Eventually, he went out on his own to sell firearms, even though he lacked a license, and got connected with Elortegui.

“It made me feel kind of strong in stature,” he said during his sentencing.

He was convicted for conspiring to smuggle and illegally engage in the business of selling firearms.

Before she gave the then-57-year-old Cummins a 40-month prison sentence in February, 2017, Judge Ann Aiken admonished him for the pain and suffering his weapons were likely going to cause. She told him it is a privilege to have the Second Amendment, and it’s regulated for a reason. She told him to read "Dreamland," which chronicles the rise in America’s opioid crisis and its connection to Mexican drug cartels.

“It's about the rust belt of the United States and what we've done with drugs, guns and opioids, because you're now part of that,” she said. “You're part of letting people come up here and put our entire country at risk.”

Illegality through legal means

Cummins' case illustrates the cost and complexity of prosecuting a straw purchase. It took a year and a half from indictment to sentencing, not including weeks of investigative work put in by federal agents tracking bank accounts and monitoring communications. Law enforcement even secured text messages of Cummins coordinating gun purchases from Adaptive Firing Solutions’s owner.

“It's all that other context that you have to use to prove this thing that on paper appears legal was a crime,” Thomas Chittum, former associate deputy director of the ATF, said. “That's why firearms trafficking cases are hard to make. Catching a felon with a gun is easy.”

Yet Republican members of Congress often look to further limit the ATF’s oversight and regulation. In May 2024, for instance, lawmakers led by Sens. John Cornyn, R-Texas, and Thom Tillis, R-N.C., introduced a resolution proposing to roll back the ATF’s ability to require firearm background checks for a wider range of gun sellers.

Chuck Grassley, the 91-year-old Republican senator from Iowa and longtime friend of the gun industry, targeted the ATF for ramping up its efforts to regulate gun sellers in an Oct. 10, 2023, letter to the agency. “Instead of encroaching on the constitutional rights of law-abiding Americans, ATF should dedicate its apparently limited resources to operations that target violent criminals and cartel firearms trafficking networks in the United States,” he wrote.

The next month, Grassley wrote the ATF again, excoriating the agency for failing to apprehend Elortegui. He outlined the case in detail as he built toward questions aimed at the agency’s competency. His timeline of events, however, redacted the text messages filed in court that might have given a fuller explanation of if and how the dealer was complicit in the sale. Grassley’s office declined to comment.

Since Cummins was sentenced, the judge’s admonishment for his role came into stark focus. Oregon’s drug overdose deaths increased year over year until 2024. Starting in 2019, opioid deaths surged in Oregon and nationwide, driven mostly by the synthetic drug fentanyl, which is 50 times more potent than heroin. In 2023, opioid deaths in Oregon peaked, nearly 400% higher than five years before.

Guns and drugs

Fentanyl and methamphetamine account for nearly all drug fatalities in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Drug fatalities peaked in fiscal year 2023 at 114,000 and were 87,000 in FY 2024.

“The Sinaloa and Jalisco cartels are at the heart of this crisis,” DEA head Anne Milgram wrote in the agency’s 2024 assessment, noting El Mencho’s cartel and another well-known one. “They operate clandestine labs in Mexico where they manufacture these drugs, and then utilize their vast distribution networks to transport the drugs into the United States.”

The link between trafficked U.S. firearms and drug trafficking is well known. Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman, former head of the Sinaloa cartel, was caught with at least five U.S.-sourced weapons in 2016. His son, Ovidio Guzmán, was caught with more than a dozen U.S.-sourced weapons in 2023. The Gulf cartel founder’s son, Osiel Cardenas-Salinas Jr., was caught attempting to purchase assault rifles in a parking lot in Brownsville, Texas, five years later. In May 2025, Guzmán pleaded guilty to federal drug charges. Cardenas-Salinas Jr. pleaded guilty in the summer of 2022.

Through our review of 100 federal trafficking cases, encompassing more than 15,000 pages of court documents, we cataloged cases that show how firearms purchased from U.S. dealers are a key link in the illicit narcotics chain. As the guns flow south, destabilizing Mexico through political violence and attacks against the country’s residents, the synthetic narcotics flow north, killing U.S. citizens.

For instance, David Campoy was a Sinaloa cartel captain of drug and weapon distribution in Southern California. He led some of his family members in a scheme to funnel hundreds of pounds of methamphetamine, heroin and other drugs from Mexico to San Jose, California, while combining firearm parts purchased in the U.S. to produce rifles with grenade launchers for family members in Mexico. His illicit connections stretched across the country from Miami, Florida, to Phoenix, Arizona, before he was apprehended in a 2021 sting. Campoy agreed to a plea in November 2024.

And since at least 2022, Maria Del Rosario Navarro-Sanchez, aka Fernanda, coordinated purchasing firearms in the U.S. with drug funds from the Jalisco Nueva Generacion cartel and the distribution of methamphetamine and fentanyl from Mexico through El Paso, Texas. During one arrest, as federal agents closed in on her drug and firearm trafficking ring, they confiscated a bag of several thousand fentanyl pills that weighed nearly three-quarters of a pound (0.33 kg) from a bedroom closet. The case is ongoing.

Related story: Gun trafficking from the U.S. to Mexico: The drug connection

What the data shows

We removed dead-end traces to large manufacturers from the ATF dataset of 15,000 guns sold in the U.S. and trafficked to Mexico. This left just under 7,000 firearms that listed U.S. gun dealers, including addresses, and that were not legally imported. Close to half the weapons records in our court database sample – just over 2,000 – listed specific firearms dealers with usable location details. The 9,014 weapons in these combined ATF and court datasets were initially purchased from more than 3,000 licensed gun sellers across nearly every state.

The majority of these firearms came from the border states of Texas, California and Arizona. A deeper dive into the data revealed trafficking hot spots that stretch up the West Coast into Washington, through the Midwest into Wisconsin and Michigan, and across the country to North Carolina and Florida.

We looked at the ATF dataset of trafficked firearms leaked from the Mexican government to get a sense of where crime guns were coming from. Yuma, Arizona, which has fewer than 100,000 residents, leads all cities in the number of trafficked guns per capita, followed by Pharr and Brownsville, Texas. All three are right on the border.

The ATF trace data, combined with the data from court records, showed that independent firearm businesses supplied 7,485 of the 9,014 traceable weapons, or 83%. This data also showed that the most dangerous types of trafficked guns originated predominantly from independent stores.

For instance, Sprague’s Sports LLC, and SNG Tactical, both in Arizona, each sold 41 guns that appear in the combined trace data. They are also two of six defendants in an ongoing RICO lawsuit filed by Mexico against firearm dealers in that state. Another dealer, Blue Steel Guns & Ammo in Missouri, was also linked to 41 firearms, but all of these weapons were the result of a smash-and-grab robbery at the gun store – the only instance of trafficking stemming from theft in the 100 cases we looked at.

In one instance mentioned in the lawsuit, Sprague’s sold multiple guns to the same man three days in a row, an indication of straw sales.

J&G Sales in Prescott, Arizona, which sells guns from a brick-and-mortar storefront and online, accounts for 39 guns in the combined trace dataset. In 2011, J&G Sales teamed up with the NRA to sue the ATF in an effort to block the requirement that border states report multiple rifle sales. In 2016, the Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence, a nonprofit organization that advocates for gun control and violence prevention, sued J&G and the World Pawn Exchange for participating in a straw purchase that led to the murder of an unarmed woman in a car in Oregon. The suit, which was ultimately settled, helped establish precedent for naming gun manufacturers in lawsuits.

Chain stores are also part of the problem. Guns originally purchased from chain stores make up 17% of the guns in the combined trace dataset, or 1,529 weapons.

Academy Ltd. is by far the biggest chain store supplier to the illicit Mexican market. It sold 369 of the firearms in the dataset, more than two times the next highest retail chain, Cabela’s and Bass Pro Shops, which sold 150.

Related story: U.S. gun trafficking to Mexico: independent gun shops supply the most dangerous weapons

We compared the combined dataset of 9,014 trafficked firearms with gun store inspection citation data obtained by The Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence.

We found that stores that had been cited for violations by the ATF were associated with fewer guns making their way into the illicit market. Our analysis found that each citation reduced guns sold to traffickers by at least 20%.

The data model we built to estimate the number of likely trafficked arms to Mexico between 1993 and 2022 also included records acquired by the nonprofit Stop US Arms to Mexico of crime guns that were seized by Mexican law enforcement in the country. The model also factored in previous trafficking estimates done by the University of San Diego, a 2020 trafficking estimate the Mexican government gave the Government Accountability Office, the number of guns sold and recovered in Mexico, and our own estimate for the number of weapons circulating in Mexico.

Our model showed that in recent years at least 72,000 weapons illegally crossed the border per year and possibly as many as 258,000 with roughly 135,000 firearms being our middle range estimate.

We compared our trafficking estimate with U.N. data on homicides in Mexico during and after the U.S. federal ban on assault weapons from 1994 to 2004. Our model estimated that for every 10,000 guns trafficked to Mexico from the U.S., the Mexico homicide rate rose by between 0.7 and 2.5 homicides per 100,000 people per year. Studies by University of Michigan and University College London researchers have found a similar relationship south of the border.

Related story: Here’s how we figured the number of guns illegally trafficked from the U.S. across the border to Mexico

The firearm industry profits from both the legal and illicit trade of firearms, and it drives an arms race between law enforcement and criminal organizations. Trafficked guns cause Mexico police to buy more guns, and more police guns cause cartel members to bring in more guns.

In 2021 the ATF teamed up with academics to produce the National Firearms Commerce and Trafficking Assessment. The studies, published from May 2022 to January 2025, detail gun commerce, trafficking and policing efforts, including ballistics, tracing and gun dealer rules.

The authors found that the share of firearms trafficked to Mexico, already the top market for illegal U.S.-to-foreign gun transfer, increased by 20% from 2017 to 2021. The last installment mapped five pipelines from Texas and Arizona to four Mexican states that account for 97% of the 18,205 recovered crime guns traced to a purchaser from 2022 to 2023.The authors found that Texas, Arizona and California were the source of 73% of the guns, with Texas the source of 43%. They found that 82% of traced Mexico crime guns were recovered in a state with a dominant presence of one of two cartels: Jalisco Nueva Generación or Sinaloa.

According to the report, trace requests for crime guns recovered in Mexico are on the rise, jumping substantially in 2022 and 2023.

In 2024, after a yearslong legal battle with the ATF, Stop US Arms to Mexico acquired data by state, ZIP code and county for firearms trafficked from throughout the U.S. to Mexico from 2015-2022. The geographic distribution mirrors what we found in our analysis. Additional data acquired by the nonprofit in early 2025 on “time to crime” – the span of time from when a gun is purchased to when it is secured at a crime scene – suggested that the number of firearms purchased for illegal trafficking increased during that time span.

“Not only is it that they're having a disproportionate impact of firearm violence in the United States,” said Eugenio Weigend Vargas, a researcher with University of Michigan’s Institute for Firearm Injury Prevention, “but it's also beyond the borders that their families are getting threatened, their families are being kidnapped, extorted with U.S. firearms.”

Guns and violence

Homicides in Mexico have risen to disturbing heights since the U.S. stopped banning the sale of assault rifles in 2004, and research suggests the two are linked. After more than a decade of declining homicide rates in Mexico, murders in the country began to shoot up in 2008. In 2022, nearly 32,000 people were killed in Mexico – a homicide rate more than three times what’s seen in the United States.

Gun sales are strictly regulated within Mexico. There are only two gun stores, and both are on military bases. But this does little to prevent violent crime because of the many illicit weapons circulating in the country, experts say.

“It's not difficult to have a gun illegally. Legally it's very complicated,” said Heriberto Paredes, a Mexican journalist based out of Michoacan, a stronghold of the Jalisco Nueva Generación cartel and smaller local cartels on the southwest coast. Paredes has seen and documented the inside of trucks loaded with assault rifles and other firearms that the cartels use to fuel their violence. “It's not a secret that it’s really easy to find a gun.”

Since the lapse of the United States’ assault weapons ban, cartels have armed themselves with high-powered, military-grade weapons and used them not only in turf wars and against the military but against peaceful citizens in shows of force and terror.

“You have these criminal actors that are involved in these types of very predatory activities where public violence is an essential part of their business model,” said Cecilia Farfán-Méndez, head of security research at the Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies at the University of California, San Diego. “The firepower becomes essential to issue these credible threats. You are not going to show up to a potential victim with a rifle that's left over from the Mexican revolution.”

Hemmed in by the Pacific Coast and Sierra Madre, residents of the rural villages Michoacan and the adjacent state of Guerrero say cartels set up checkpoints to control the flow of traffic along mountain roads leading into towns and villages – areas difficult for most state forces to enforce the rule of law.

In the summer of 2023, Juan Gabriel Alarcon-Avila lived with his wife, Alicia Zomora-Guevara, in a small town in the mountains of Guerrero and made soccer balls with his son, Kevin Jait Alarcon-Zamora, carrying on the family business established by Alarcon-Avila’s father.

But in recent years the community has been terrorized by cartels. A boy who worked in a butcher shop was taken by a cartel, the family said. The next day, his body was dropped inside the community without his arms and eyes – a common tactic among modern cartels that look to sow fear throughout Mexico.

And on June 28, 2023, seemingly without warning, Alarcon-Avila’s family and people related to him were attacked, according to interviews with the family, ostensibly because someone sharing his family name had wronged the La Familia Michoacán.

"Everywhere in town they were shooting and throwing grenades," Zomora-Guevara said.

Down the road, their niece, Emylce Ines Espinoza-Alarcon, a mother of three, was also under attack. Bullets flew through her home. She grabbed her 9-year-old son.

“When I woke up, I heard bullets, and I asked my mom, 'What's going on?'” her son, Victor Hugo Galgado-Espinoza, said. They fled their home and hid alongside a road through the night.

“I heard people screaming. I could hear them shooting. I was watching them shoot up my house,” he said.

The next day, community members hid the family but told them they could not stay, the family said. The relatives and family of Alarcon-Avila are now internally displaced within Mexico. Their homes were burned down after they left, and more residents have been driven out.

“We look to the United States,” Zomora-Guevara said.

"People here think that it's a place that guarantees rights and guarantees life.

But then when we learn the weapons are coming from there,

then that lets us know that it is a country that doesn't guarantee life for people in Mexico."

After her mother was killed by organized crime five years ago, Espinoza-Alarcon said, her sister migrated to the States with her husband and daughter. They have a stable life, and her sister is working.

“My children continue to grow up and they have that trauma. As a parent, you try to flee to a different place where they might be safe," Espinoza-Alarcon said. She believes American weapons drove her from her home, but there “is nowhere else for us to go."

A 2023 survey found that 88% of the 180,000 Mexican migrants to the U.S. that year were fleeing violence – a flip from 2017 when most were coming for economic opportunity.

Laura Vargas, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado, has spoken with about 300 migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border documenting the traumas they’ve experienced.

Vargas said she has noticed a shift from predominantly single adults looking to earn money in the States to send back to their families to more people traveling with their families or sending children unaccompanied. Encounters of families and unaccompanied minors jumped 220% from 2017 to 2023, peaking at just over 1 million, before dipping below 700,000 in 2024, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection data.

“Why would people from every walk of life choose to leave – even those who have a good life? The answer is violence,” she said. “You would probably cut migration in half if you were to put some kind of regulation on firearms.”

Gun dealers

Around 2007, Richard Haught, a high school dropout who supported himself through woodworking until back surgery derailed his livelihood, was prescribed opioid pills for postoperative pain. The prescription led to an addiction as he moved from hydrocodone to oxycodone.

He got involved with trafficking arms to Mexico for cash to support the addiction and convinced his younger brother, Robert Haught, to join. Robert took over and recruited his wife and her brother after Richard landed in jail on a drug-related charge.

In Ohio federal court documents they were dubbed the Indiana group, a coalition that purchased Barrett military-grade firearms from dealers in Indiana, Illinois, Ohio and Pennsylvania and transported them to McAllen, Texas, where the serial numbers were obliterated and the weapons resold for export to cartels. Between Jan. 29, 2014, and March 20, 2015, they trafficked more than 70 high-caliber weapons that would retail for more than $650,000.

“These weren’t rifles for weekend hunting or sport; they were, for the most part, .50-caliber semiautomatic rifles and civilian versions of belt-fed machine guns – weapons of war,” U.S. attorneys wrote in a court filing.

Paul Groves, operator of gun dealership High Powered Armory in Youngstown, Ohio, was willing to sell the group batches of weapons for cash as long as they filled out the required paperwork at his store. His sales to the group included 62 Barrett .50-caliber rifles.

During some purchases a member of the Indiana group had an undercover ATF agent in tow. The feds suspected that Groves and partner Eric Grimes were illegally manufacturing firearms at a second location. When agents raided the establishment, they uncovered dozens of firearms, including 43 illegal machine guns. Hard drives showed that Grimes had done business with about 90 people. They later seized 28 illegal machine guns and parts manufactured and sold by Grimes in Las Vegas and Casper, Wyoming.

Grimes accepted a plea deal for a days imprisonment plus fines in late 2017 for testifying in a potential trial against Groves. In January 2018, Robert Haught was sentenced to 57 months in prison, and Richard 64 months. In Richard’s sentencing memo, the prosecution mused, “We will long wonder what terror those .50-caliber semi-automatic rifles might have wrought once they got to Mexico.”

Groves said he didn’t know about the Indiana group’s machinations. An investigation turned up texts about the group being annoyed that Groves was making them do so much work to complete the purchases. The evidence showed that Groves did everything by the book. Groves pleaded guilty for owning one unlicensed machine gun.

“I’m gagging on what’s being crammed down my throat here,” Judge Michael Watson said during Groves’ sentencing hearing in July 2022. “There are 60 firearms that wound up in the hands of the cartel that I am supposed to just smile and accept here.” Groves was sentenced to nine months plus fines.

Two weapons associated with Groves and Grimes through their gun dealerships appear in the Guacamaya leak data, and the case isn’t an anomaly, based on our analysis and reporting.

“It's life as an ATF agent,” said Michael Bouchard, former assistant director for the ATF’s field operations, a position he left in 2007 after 25 years. “You know how many dead people are going to be from all these .50-cal. machine guns out there, and he played a part in it?” Bouchard is now president of the ATF Association, an independent support organization for ATF employees and retirees. He also advises gun dealers on how to comply with regulations.

Unscrupulous dealers can exploit firearm laws to legally sell large numbers of weapons, often for untraceable cash. With the Gun Control Act of 1968's requirement that ATF approve or deny a firearm license application within 60 days, dealers can shut down and quickly relocate.

Joshua Kimball ran a gun shop in Huggins, Missouri, a township with fewer than 200 residents. When federal agents started asking Kimball about the multitude of his weapons showing up at crime scenes in 2021, he closed up shop and established a new dealership, Show Off Sports, in Bakersfield, California.

Almost as soon as the new location showed up in ATF records, firearms began to surface at crime scenes throughout California, Nevada, Arizona and Mexico. They appeared at street gang shootings in Southern California, with neo-Nazi bombers in Fresno, with Armenian drug traffickers in Los Angeles County, and even in the bathroom of a department store in Mexicali, Baja California.

When federal agents did an undercover sting of Kimball's Bakersfield establishment in the fall of 2023, he told them that his business was more of a “sports association” with a membership fee where gun enthusiasts could “walk in, walk out” when they wanted to buy a weapon or “off-roster guns.”

Kimball told agents he wanted to start his own franchise to attract “the hardcore guys that got a little shop” and “they’re not chasing the money. These guys are competition shooters, they’re avid hunters, they’re law enforcement, it’s guys that got into the business to do the right thing.”

He had the undercover agents fill out a contact form so that “if something weird comes up, you have to work with us,” such as getting contacted by law enforcement or shooting someone. Or “if you’re going through a divorce, and you get a restraining order, grab all your shit and come down here and drop it all off.”

As of spring, 2024, more than 139 firearms related to Kimball had been recovered from crime scenes – up from 103 at the time of his arrest. But more than 900 guns associated with Kimball are unaccounted for. He pleaded guilty to firearms trafficking in March, 2025

The ATF’s enforcement

In 1968, after the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and U.S. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, a bill that had been on the books since President John F. Kennedy was assassinated five years earlier was rushed through Congress and signed into law, establishing the Gun Control Act of 1968 and adding firearms to the bureau’s growing list of oversight.

That turned less than 20 years later. Riding the wave created by the Right to Keep and Bear Arms report and fear generated by a historically high murder rate, the Firearms Owners’ Protection Act was introduced in 1985 and passed by Congress in March 1986 as one of the biggest rollbacks of firearm regulation in U.S. history. The act allowed for the interstate sale and transfer of firearms and allowed firearm sales at gun shows.

The act also drastically reduced the power of the ATF. It loosened the restriction on who could legally sell guns, limited the agency’s authority to revoke firearms licenses and capped general compliance inspections to a maximum of one per year.

And inspections are a key method to keep illicit guns in check, our analysis shows.

The agency’s primary enforcement tools, in addition to doing inspections, are issuing violations reports, sending the firearm licensee a warning letter, having a warning meeting with the licensee, and, when inspectors find violations that are reckless or willfully endanger the public, sending a notice of revocation.

Stretching back more than two decades, the Justice Department Office of the Inspector General has consistently found that the ATF inspects few firearm dealers. Even after improvements were made, it found in 2013 that 58% of firearm licensees hadn’t been inspected within five years.

The ATF faces frequent allegations that its enforcement actions are driven more by politics than efficacy.

Gun owner association types in the U.S. “have long wanted the ATF to wither and disappear,” said Kathi Lynn Austin, arm-trafficking expert and founder and executive director of the nonprofit Conflict Awareness Project, which investigates arms trafficking. The ATF “would need more power to be better enforcers, but the powers that be don't really want them to have that power, so they're kind of stuck in a catch-22.”

The ATF undertook a renewed effort in 2013. Yet a 2019 review of that initiative found that it suffered from a lack of internal intelligence sharing and effective data collections – a sentiment echoed in a 2021 Government Accountability Office report.

And a 2023 GAO report noted that more than 2,000 of the country‘s 75,000 gun dealers hadn’t been inspected from October 2010, to February 2022. “ATF is at risk of fostering the perception among gun dealers that certain violations are tolerated,” the report’s authors wrote.

In 2021 the Biden administration announced the gun crime prevention strategy that strengthened the ATF’s ability to revoke licenses of firearm dealers, creating a zero-tolerance policy that revoked firearm licenses from dealers who broke the law, and the ATF has dramatically increased the number of revocations.

After mass shootings at the Tops supermarket in Buffalo, New York, and Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, in May 2022, Congress passed the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, which made it more difficult to sell guns without a license and established the first federal law prohibiting firearm trafficking.

After being sued by a gun dealer, the Biden administration softened the zero-tolerance revocation policy in mid-2024 by giving inspectors more discretion.

There were only 674 ATF industry operations investigators working in the field at the close of the agency’s 2023 fiscal year – or 111 gun sellers per inspector, not counting thousands of specialty dealerships and explosives sellers. The bureau’s 2025 congressional budget request points out that the bureau would need 1,509 field investigators to complete its goal of inspecting each dealer at least once every three years.

While the ATF has some enforcement data on their website – including until recently a listing of current firearms dealers and documentation around those who have had their licenses revoked – the laws restricting more detailed data to be collected has made it difficult for the public and researchers to get details on which gun shops have been subject to enforcement actions short of revocation. In contrast, many government agencies, including the EPA, Department of Labor and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, make detailed data on enforcement activities available to the public and researchers for independent analysis.

“ATF’s approach prioritizes public safety by focusing on identifying and addressing willful violations that pose significant risks,” an ATF spokesperson wrote in a November 2024 emailed response to The Conversation’s findings and questions.

The bureau chooses which firearms dealers to inspect using crime gun intelligence analytics, she wrote. These crime gun patterns include the length of time between when a gun is sold in the U.S. and when it shows up in a crime scene in Mexico. “Additionally, ATF employs a rigorous, multi-step process that emphasizes corrective actions and compliance support before resorting to license revocations, reflecting our commitment to a fair and consistent regulatory framework,” she wrote, referring to the zero-tolerance revocation policy that went into effect in 2021.

The ATF announced in April 2025 that it was repealing the revocation policy and reviewing recent ATF rules that clarify when a gun is a rifle and define who is engaged in the business of dealing in firearms. The webpage listing revocations and details about the gun dealers who have their licenses revoked was also removed from the site in April.

The bureau remains resource- and cash-strapped, and its work has exploded, while it continues to be hamstrung by earlier laws. For example, the Tiahrt Amendments bar the ATF from having a centralized, searchable database of records, including from dealers that have gone out of business. As a result, it keeps thousands of boxes of paper records in one of its offices and must regularly move some to outside storage to keep the floor from collapsing.

The data

Related Stories

U.S. gun trafficking to Mexico: Independent gun shops supply the most dangerous weapons

Gun trafficking from the U.S. to Mexico: The drug connection

Here’s how we figured the number of guns illegally trafficked from the U.S. across the border to Mexico

Authors

Investigative journalist

Professor of Economic Development and Peacebuilding, University of San Diego

Disclosures

Sean Campbell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations.

Topher McDougal does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond his academic appointment.